In a pub just south of nowhere, in a town not far from here,

I was deep in contemplation at the bottom of a beer.

My life was going nowhere, I was lost and I was broke;

I was down to my last dollar, I was down to my last smoke.

My wife had up and left me, took the dog and took the kids,

Said she wouldn't have a future with a bloke who's on the skids.

Then she talked about young Ted and Kate, and it got me boiling mad

When she said they'd never make it with a loser for a Dad;

Said the boozing and the gambling and the womanizing too,

Were more than she could handle. Then she simply said, "We're through."

So I sat there feeling empty, and my beer was almost gone

And inside a voice was saying, "There's no reason to go on."

"There's no one here who'll miss you," whined that voice inside my head.

"You're just a flamin' waste of space; you might as well be dead."

So I planned just how I'd do it, and I saw no need to wait,

And I turned toward the barman and said, "See ya later, mate."

But as I stumbled t'ward the door, a voice rang in my ear,

Saying, "How're ya goin', cobber? Would ya like another beer?"

So this old bloke fetched a bottle and he said, "My name is Jack,

But most folks call me Smiler. No, I don't need payin' back."

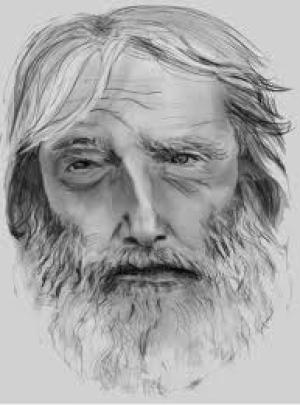

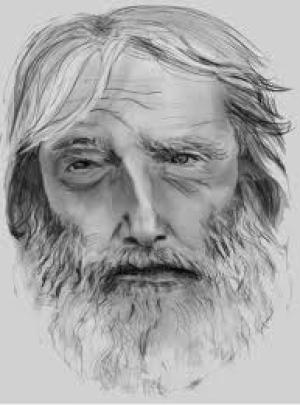

Though his face was tanned to leather and his hair was snowy white,

His voice was strong and steady as he talked into the night.

"I was raised in the Depression years, when my Dad for work would roam.

Then he headed north to Queensland and he never came back home.

My Mum grew old before her time raisin' me and brother Bill,

Until she died of snakebite; I remember that day still.

In thirty-nine the world went mad and we were called to war,

And after training, me and Bill shipped out to Singapore.

When the Japanese surged southward in their cruel, relentless tramp,

The garrison surrendered; we were penned in Changi Camp.

But Bill he caught a fever and he lost the will to live;

My only family dead and gone; I had no more to give.

Then the Japs took all us prisoners that were fit to draw a breath

And they sent us off to Burma to build the Rail of Death.

So we built their bloody railway but at what a fearful cost.

It seemed for ev'ry sleeper laid, another life was lost.

And at times we got so hungry we'd eat weevils mixed with grass

While we dug through rock with our bare hands at a place called Hellfire Pass

And when the war was over, I just couldn't settle down;

I must've had a hundred jobs, I roamed from town to town.

But then one day I met my Ruth, who soon became my wife;

She soothed away the nightmares; she eased the pain and strife.

Well I thrived on that contentment and I lost the urge to roam.

We raised a son, I named him Bill, we built ourselves a home.

Another war and Bill was called to fight in Vietnam

"Killed in action," starkly read that awful telegram.

They say that grief can't kill you, and that time will dull the pain,

But until the cancer took her, Ruth was never quite the same.

It's twenty years now since she died; I miss her every day."

The Smiler paused and wiped his eye and turned his gaze away.

We sat a while in silence, then he spoke to my surprise;

He said, "Son, I see you're hurtin', I can read it in your eyes.

You have to play the cards God deals you, some are aces, some are two's,

But you never throw your hand in till you wear a dead man's shoes."

I thanked him for the drinks, and he said, "Mate, that's quite alright."

Then he shook my hand and vanished, just walked out into the night.

So I asked the man behind the bar if he knew who Jack could be,

And he looked at me quite strangely, took a breath or two or three.

"I know the bloke you're meanin'," said the barman with a frown,

"Ol' Smiler Jack's a legend; he's the man who built this town.

But I dunno how you saw him, don't suppose you ever will;

He died last year. We buried him by the church up on the hill.

You've been sittin' in that corner twenty minutes at the most,

And I think the drink has got ya; you've been chattin' with a ghost."

In the morning I went searching and I found the place at last

A little granite headstone nestled snugly in the grass.

And I traced the brief inscription with my finger as I read;

"Gone to meet the Dealer," were the simple words it said.

So I called my wife that evening and I begged for one more chance.

I told her I was sorry for leading such a dance.

I explained how much I missed her, missed the kids and missed the dog;

With her help I'd beat my demons - the gambling and the grog.

Then she cried and said she loved me, and so did Ted and Kate;

Said she'd meet me in the morning and I'd better not be late.

So I slept that night a happy man, my life was back on track,

And I owed it all to the man they call the Smiler - Smiler Jack.

|

Author Notes

Revived story poem.

One of my keenest ambitions on FanStory is to win the site contest 'Share a Story in a Poem'. I thought this one might have a chance but obviously the committee disagreed....

For your delectation, I also wrote an alternative (and more likely) ending. That is reproduced as a separate poem called 'Who's Smiling Now' as the next chapter in the book.

This is written in Australian English, and I have tried to reproduce the Australian drawl for some of the characters - I don't think any of it is too difficult to understand.

The Death Railway is a 415 kilometres (258 mi) railway between Bangkok, Thailand, and Rangoon, Burma, built by the Empire of Japan during World War II, to support its forces in the Burma campaign.

Forced labour was used in its construction. About 180,000 Asian labourers and 60,000 Allied POWs worked on the railway. Of these, around 90,000 Asian labourers and 16,000 Allied POWs died as a direct result of the project. The dead POWs included 6,318 British personnel, 2,815 Australians, 2,490 Dutch, about 356 Americans and a smaller number of Canadians and New Zealanders

|

|